The Religion of Reason

A cursory and critical appraisal of the Enlightenment, and how it now drives Transhumanist hubris

This substack, in large part, is the substance of the first seminar paper I prepared for a semester postgraduate studies’ course in the Dept of Religious Studies at the University of Cape Town in 1989. I was starting my Master of Arts programme with a selection of courses to complete. This course was entitled: ‘Christian Studies: The Enlightenment to the Present.’

[I may consider publishing some more seminar papers in the coming weeks for readers who may have an interest in this subject matter.]

Dare to know!

The resounding motto of the Enlightenment is captured in Immanuel Kant’s exclamation: “Sapere aude! (Dare to know!). Have courage to use your own reason!” (Livingstone 1971:1) New confidence characterised humanity’s search for truth, more particularly for the true, universal religion.

What was unique about the 18th century was not so much a discovery of the mind in exploring religious truth. For this also typified the earlier Classical, Medieval, and Renaissance periods. Rather, the uniqueness was in “in the way in which (humanity’s) rational faculties could be used to achieve certain specific ends” (Cragg 1970:235-236) which until that time remained largely under the control of external forces. Notorious among these forces were institutionalised ecclesiasticism and clerical dogmatism and intolerance, exemplified very strongly in Medieval scholasticism and Protestant orthodoxy. But now reason re-emerged as the dynamic force which creatively an critically functioned to reinterpret all known beliefs and ideas, and to usher in a new age of human understanding. It was believed that humanity had at last been emancipated from its “self-incurred tutelage.” (Livingstone 1971:1). “It proclaimed the autonomy of man’s mind and his infinite capacity for progress and perfectability.” (Cragg 1970:234)

A radical shift

The radical shift which marked the onset of the Enlightenment was due essentially to two revolutions of far reaching importance.

Firstly, there was the scientific revolution of Copernicus, Galileo and Newton which heralded a fresh interpretation of humanity’s pride of place in a well-ordered, mechanical universe.

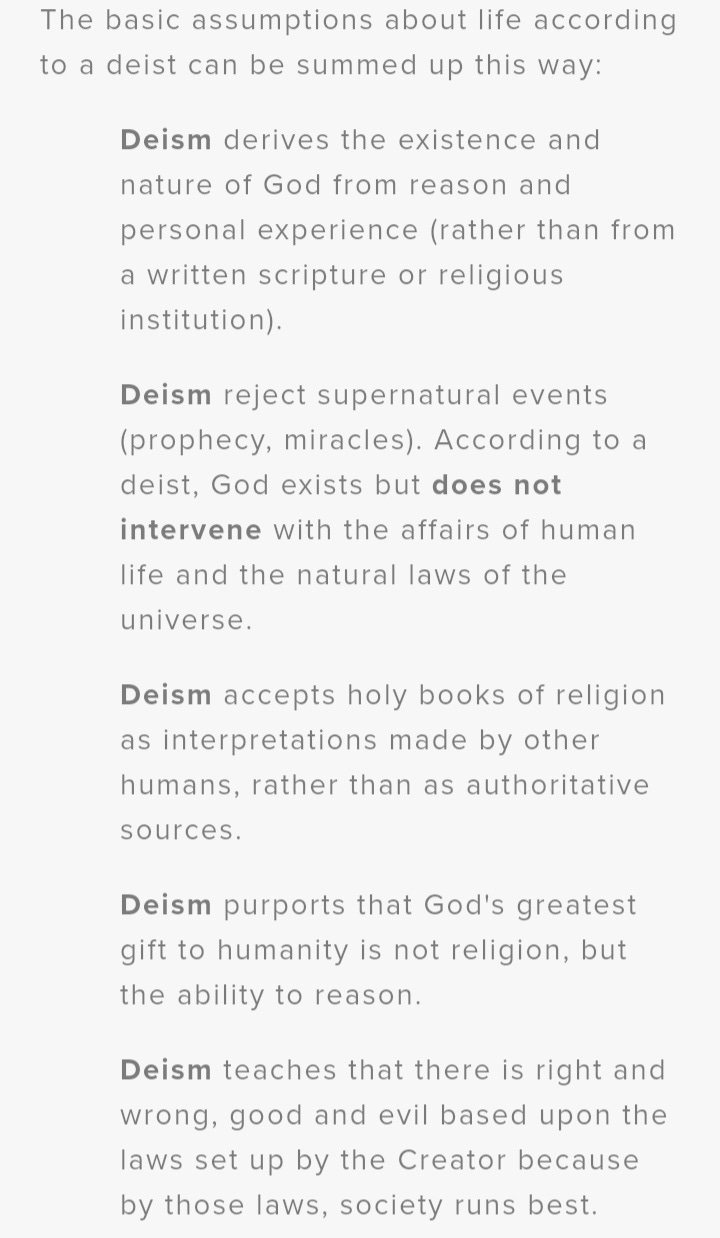

Here natural laws became the primary test of truth. Now humanity’s ideas and its institutions were all judged by their conformity with these laws. No contradiction was now seen between the rational and the natural.

To guarantee the sense of order and motion in the universe, Deism proffered a ready solution. God was not rejected, but rather domesticated. In other words, God stood completely outside human history, disconnected from a world where humanity enjoyed free control, but God nevertheless maintained the order in the cosmos.

One may inquire why God was posited in the first place, since a complete rejection of God (as later developed atheism proved) did not mean the sudden chaos in the universe. One motivation for accepting ‘God’ was probably due to the Christian heritage which most Enlightenment thinkers shared in. Hence their reluctance to dispense with theism altogether.

Cragg (1970:237) critiques the “glorification of the Newtonian revolution” as “having ‘deified nature’ and ‘denatured God’.” While this criticism is valid, it does convey a prejudged perspective of 18th century thought and does serve to neutralise or camouflage the positive features of this period.

Secondly, the Cartesian revolution made doubting the first principle of philosophy and the model of the sciences. Consequently, unbelief was now defined, not as the doubting of former religious truths handed down, but rather in the persistent toleration of narrowly defined beliefs and the rejection of all others. (Cassirer 1951:164)

Therefore, the traditional view of the Enlightenment as an age characterised by “a critical and skeptical attitude toward religion” is a limited one, and precipitated more by a fixation on the extreme statements of French philosophers like Voltaire and Diderot.

This view ignores the positive and needed impact of the Enlightenment which is demonstrated not in its irreligious character so much as in its rational spirit which took seriously the presiding questions of the day.

The matter of authority

However, in seeking critically to address what it saw as the superstition and fanaticism in orthodox Christianity, the two major streams of the Enlightenment – the rational supernaturalists (to a lesser degree) and the deists (to a greater degree) tended toward varying intensities of anti-Christian feelings. The crucial concerns which initially gave impetus to such feelings were legitimate ones. ‘Where is authority vested in the world?’ ‘Where does authority come from?’ Restated from a Christian perspective, ‘What is Christianity?’ and ‘What is the essence of Christianity?’ ‘ What is its authority?’

In the varying attempts to answer such questions and in its process of reconstructing an ‘acceptable’ Christianity for the Age, French Deism became decidedly more anti-Christian and belligerent than others. This was primarily due to the increasingly strong opposition from the Church in France to the rational spirit there. Here the Church had established itself firmly as the arbiter of what the final authority in religious matters was. Inevitably and reaction to this, Christianity was rejected as “a corruption of true religions” and “an evil to be opposed.” (Livingstone 1971:36).

English Deism, embodied in the thoughts of Toland and Tindal, was more constructive. It identified Christianity with the religion of nature (Livingstone 1971:36). While historical revelation (especially the Bible) was not rejected as was the case with the extreme positions of French deism, the former was wholly subordinated to the religion of reason. It served only as “a mere convenience or concession to human weakness.” (Livingstone 1971:36).

The rationalism of German Deism may have started with the radical criticisms of Reimarus in his virtual elimination of both the historical reliability of the biblical text and the Christian faith. But with Gotthold Lessing it went beyond the mere criticism of Scripture or the re-evaluation of Christianity. Instead, Christianity was conceived as one progressive stage in the history towards the realisation of “the perfect universal religion which lies in the future.” (Livingstone 1971:36). Recognising the grave problems discovered with the biblical texts, Lessing sought to free Christianity from being equated with the Bible or historical facts. Affirming his own predisposition to the rationalist spirit of the time, he posited the idea of the “ugly, broad ditch.”

This was not a rejection of historical facts per se, but rather the presupposition “that truths in the absolute sense cannot be historical. No jump can be made from historical to necessary truth.” (Bromiley 1978:345). Restated, “accidental truths of history can never become the proof of necessary truths of reason.” (Livingstone 1971:32). The authority moves from any external authority to that inward truth within religions which determines its authority. In this way, the milder form of the religion of reason, namely of the rational supernaturalism of people like Tilloston and Locke – who laid stock on “the historical testimony of miracles and fulfilled prophecy” (Livingston 1971:31) as important in accrediting the authority of the Bible and Christianity – was rejected. The overriding rationalist assumption which grew and became a hallmark of Enlightenment thought is captured in the exaggerated confidence of Lessing:

I live in the Enlightenment century, in which miracles no longer happen. – (Livingstone 1971:32)

Only at best, we have testimonies of miracles which others provide! Among the pressing incentives for this view was the shift from the social or institutionalised control of religious truth towards the complete autonomy of these truths themselves.

Reason and conscience became the primary arbiters of truth and action. – (Livingstone 1971:3)

Morality and the rise of ‘historical consciousness’

Morality arose inevitably as a criterion of religious truth.

Religion becomes the recognition of our moral duties as divine commands. – (Livingstone 1971:24)

Also, emergent rationalism of the 18th century was combined with “an empirical spirit” (Livingstone 1971: 39) which moved beyond the rational speculation of Cartesian philosophy, and introduced a strong “historical consciousness” (Livingstone 1971:31). This sense of history or the shaping of all truth by particular events of history made less obvious the need for revelation which could not be empirically tested.

The definitions of John Locke provided a helpful guide. That which contradicted reason was rejected. That which was beyond reason made necessary the supplement of revelation. This retained the element of mystery which was believed to be inherent in Christianity in particular. The dominant perspective, however, was that anything which accorded with reason characterised the chief character of religion in which humanity as a whole could share.

The religion of reason was, therefore, that religion which was brought under the greater control of natural reason, and made to rely less and less on revelation. In this way it was believed that stability in the world could be guaranteed, religious wars eliminated, and all forms of divisiveness overcome. Anything which inhibited the progress towards universal, natural religion was wrong.

It would be Kant’s ‘Critique of Pure Reason’ which would, most profoundly, shatter the exaggerated confidence in the ‘religion of reason’ movement.

A critical evaluation

The ‘religion of reason’ of the 18th century had both its strengths and limitations.

Among its strengths was how it succeeded in overcoming the exaggerated pessimism about the world and about human nature which had characterised much of Reformed theology in the 16th and 17th centuries. The consistent appeal to autonomous reason largely overcame the pseudo-rationalism in Protestant scholasticism which had strangled the life-blood from theological orthodoxy.

There were several weaknesses. One was the inability to come to grips sufficiently with the theodicy problem. In this way, the ‘religion of reason’ encouraged too strong an optimism among human beings. Human effort and intellectual progress alone could overcome evil and suffering in the world without direct need for God. Even the more cautious ‘melioristic optimism’ (Livingstone 1871:6) of Voltaire formulated in the wake of the Lisbon earthquake in 1755 was too optimistic. In this sense, the ‘religion of reason’ failed to address adequately the challenge of ‘original sin’ and ‘the Fall’ which the Reformation had reaffirmed. Also, ‘the dogma of reason’ which the Enlightenment had wittingly or unwittingly established for itself was largely incapable of overcoming the incisive attack levelled at by the ‘skepticism’ of Scottish philosopher, David Hume. He exposed “the bankruptcy of eighteenth century reasonableness” (Brown 1968:70). Although the attempts to make religion a simple matter freed from institutionalised control and more accessible to the individual was noble, it is doubtful whether this occurred for the majority of people, especially the poor and marginalised. Remaining largely bourgeois itself and being restricted to “a philosophic family” (Gay 1966:6), the ‘religion of reason’ often eliminated or weakened the faith of the poor while failing to replace it with an alternative faith that was more liberating.

And so, bringing this cursory and critical appraisal of the Enlightenment into our current 21st century times, we can conclude with a warning from Canadian historian and author, Matt Ehret. In his illuminating interview, “From Enlightenment Corruption to Cybernetics Fusion” (18 July 2023), Ehret states:

We are told that we are living through the emerging “Fourth Industrial Revolution”.

In this transitionary period, we have been told by borg-like technocrats that humans will merge with the machines engineered by social engineers, and that we as biological machines, will be part of a new "organism" mixed of metal, plastic, silicon and flesh.

This new species of “transhuman” will be liberated from all outdated ideas of Soul, morality, freedom, free will or any relationship with the Divine.

We are assured by priests of this new technotronic age that everything is determined for us by DNA, all is pre-programmed in the Great Book of Random Evolution (written by nobody) and the result is inevitable, unavoidable and absolutely inescapable.

This perspective justifies top down intervention and control, by an oligarchic elite Enlightened by Modern Reason (which gained cultural preponderance in the Enlightenment Hubris, also giving rise to the modern utopia of liberal democracies). The Enlightenment Hubris that flowed into the technocratic illusion that we are told is the only solution for the organization of society, the world, the planet, and our biological and cybernetic progression.

You can access the Matt Ehret interview here: https://www.bitchute.com/video/luPnh6J3uXFK/

I close with a poem:

Beyond Hubris

Each of us, perhaps more than once,

In the journey of a life time,

Has built our own tower of Babel,

Reaching for that sweet taste of a god-like glory,

Wearing that dazzling crown, bright with

The sheer magnificence of our own success,

All around, the allure of adoring adulation,

And the pomposity of just this moment,

Though we often crave for more and for longer;

Hubris flows so sinister in all our veins,

Coursing surreptitiously through our frames,

Pumping our egos with arrogant audacity,

Driving our humanity with a grandiosity,

At the centre of this universe

Of our own creation, we demand more

Attention; the intoxicating applause of galleries,

High, we perch on our lofty self-importance,

We savour the eyes of the watching world on us;

And through time, each of us, with this hubris,

Feeds empires that bloat and boast,

Puffed up and swollen with conceit,

Mesmerised, we join in flattery of our invincibility,

We groom ourselves in fanciful visions of immortality,

Puffed out, we survey all that we have made,

We believe our destiny is the dominance of the stars,

We stand, Caesar-like with clenched and iron-clad fists,

We lord over creation with postures of our pride.

But our hubris is the mocking of our true being,

Look! The mirror is cracking under the falsity of our gaze,

Right now, we are called to see anew, with humble eyes,

The sacred light wants to shine in and permeate our souls,

She wants to realign us with our one essential self,

At last! The tempter’s hypnotic voice is overcome with Spirit’s grace,

Our true humanity is freed and unfolds within Creator’s realm,

Now, we know ourselves enshrined in Spirit’s majesty and love,

We bathe in the Presence, both within and from above.

We dare to journey on through these pleasures and these pains,

We step into our higher calling, and into more noble gains.

© Roger Arendse – 20200502

References:

Bromiley, G.N. 1978. Historical Theology – An Introduction, Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B Eerdmans Publishing Company

Brown, C. 1968. Philosophy and the Christian Faith, Downer’s Grove, Illinois: IVP

Cassirer, E. 1951. The Philosophy of the Enlightenment, Ch. IV, USA: Princeton University Press

Cragg, G.R. 1970. The Church and the Age of Reason 1648 – 1789, Great Britain: Penguin Books

Gay, P. 1966. The Enlightenment – An Introduction: The Rise of Modern Paganism, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson

Livingstone, J.C. 1971. Modern Christian Thought – From the Enlightenment to Vatican II, Ch. 1 – 2, New York: Macmillan Publishing Company